This month, my goal is to get people to understand the idea of the fancy term "Proof by Induction" and what "proofs" generally are.

With any type of work online, I do have to give a disclaimer: I am a math graduate student with a B.S. in Math, but I am not the end-all-be-all of this topic. I will most likely say something wrong, but the point of this project is to level math in a way that is understandable, perhaps at the cost of rigor and nuance.

Think about something that you know to be true, for example, “the day after Wednesday is Thursday.” You can prove this statement with one line, “By definition of the English week day names, it follows that Thursday is the day after Wednesday”. This may seem too simple, but I would consider this a “proof”. The idea is to use facts that you know already and piece things together to make a logical argument.

If we want to go a step further, another example would be proving “0 is less than 2” using the puzzle pieces “0 is less than 1” and “1 is less than 2”. My intended proof goes something like, “Since 0 is less than 1 and 1 is less than 2, we can say 0 is less than 1 is less than 2. We conclude that 0 is less than 2.” George Nasr, my graduate student mentor, points out that you can prove this easily without using those jigsaw piece. You can say “nothing is less than something” and get the same result. The beauty of proofs is that there is more than one way to prove the same thing!

Proofs in higher mathematics get a lot more word-y and it looks less like your typical math class and more like an English class. But the idea should stick that it is only using puzzle pieces that we already have to construct a known (or in amazing cases: new) jigsaw puzzles.

I chose to talk about “Proof by Induction”, because this is the first proof that people usually learn and it is the first time I did not understand something in Math.

You could call the Wednesday proof as “Proof by Definition”, while my intended Zero proof is “Proof by Transitivity (of the Less Than Relationship)”. (Quick rough note: Transitivity is this relationship that if A is related to B and B is related to C, then A is related to C.) Proof by Induction uses a specific type of puzzle pieces and relationships, and this relationship is what is initially confusing. Google defines “Induction” as “the process or action of bringing about or giving rise to something”, which is absolutely confusing.

To me, “Induction” means “if one thing happens, another thing follows”, think like a domino effect. So, “Proof by Induction” is a proof that relies on establishing a domino effect. (Later we will see that we have to be careful about how to do this domino effect, but for now this is a good image.)

I actually could not find a good example for how to use induction in real life scenarios. Let us be lame and just use dominos as a guiding non-math example. Suppose that we arrange a collection of dominos so that they are placed in a line, like a typical domino YouTube video. Let us prove that for any number of dominos, if you tip the first domino, the rest must fall.

With every “Proof by Induction”, we start with the “base” case. You can think of this as a check that the beginning case is true. So, if we have one domino, then we know if we push it, it will fall. Then done! We just saw that it is true that with one domino, all of it (the one) will fall.

So, we have the base case true! Let us move onto the next stage of Proof by Induction. Welcome to the fancy “Inductive Hypothesis” step. In this case, we start by saying (something along the lines of) “Suppose we know that with N amount of dominos, all of them will fall”. Then, the next thing to do is to show: if we have N+1 dominos and we know what happens with N dominos, that N+1 of them will fall.

Now, we know that attaching one more domino will not affect the outcome since the N-th one will hit the N+1-th one and cause it to fall. More specifically, the first N will fall (by our Inductive Hypothesis) and the Nth domino falling causes the (N+1)-th to fall. So, we have that even with N+1 dominos, all of them will fall after the first one is pushed. So, we have done Proof by Induction! We have that no matter how many dominos we have, we know it will all fall! It could be 1, 10, or a million. We know it will all fall.

Remember when I said we should be careful about establishing the domino relationship? We are going to see an example, where we assume that a relationship is true for all cases, but we just got lucky with the special cases.

Take the statement “Every odd number is a prime number”. (Side note, apparently 1 is not a prime number and this is not an essay on prime numbers, so I will not be delving into that.)

Before we move to the Base and Inductive Steps, let us imagine we have this machine called PrimeBox that tells us instantly if a number we give it is prime or not.

In the base case, we have that 3 is the 1) first 2) odd 3) positive and 4) prime number. If we feed 3 into PrimeBox, it will say Yes! So our base is done. The inductive step is to assume that we know the N-th odd number is prime, so let us look at the (N+1)-th odd number. But our PrimeBox complains. What is wrong? The numbers 3, 5, and 7 are all good numbers for our PrimeBox. But the next odd number is 9 and it has the nifty property of being 3 times 3 so it is not a prime number.

One of the main issues here is also that PrimeBox does not exist for abstract numbers. For example, what IS the N-th prime? And how do you create a machine that tests prime-ness of an abstract number, all machines we have need a tangible presentation of it. Programming codes cannot work with something that is not concrete, and even mathematics has no way to easily list all the primes since they do not have an inherent (known) pattern.

So, why could we do it with the dominos (and other well-behaved Proof by induction)? Because that domino relationship was something we could count on, given that the dominos are spaced enough that one will push the next. We were confident that it would continue to happen, because we already had an idea (“conjecture” would be a Math word here) that it would. But the odd prime number example is where we did not have this confidence, we relied heavily on induction to do the heavy lifting of confirming this confidence. In other words, there was no way of using the Nth event to inform the (N+1)-th event. It is almost as if the dominos for odd prime numbers were not spaced enough that one will push the next.

So from my experience, Proof by Induction is not that great of a tool outside of things that have been specifically curated to either make it useful or show why it is bad to assume. But what it hopes to accomplish is to practice this idea of building blocks and puzzle pieces in proofs. First relying on a fact that you know is true, then using that to establish something new and hopefully stronger.

In this poetic sense, my relationship with Mathematics is from this idea: we have building blocks and known facts, and we are given a problem or an issue to solve. We have to find which of these pieces will be useful for us and how do we break the problem apart into its own pieces. The ending result will be a new complete jigsaw puzzle, where you used all the pieces from the problem and maybe old pieces that you already knew before.

We will look at an example that works and is in math! Take the positive numbers from 1 to some larger integer N, then the sum of all those numbers from 1 to N is N(N+1)/2. In other words, we are going to prove that 1+2+...+N = N(N+1)/2.

Base case is when N=1. Then if we plug it into N(N+1)/2 = 1(1+1)/2 = 2/2 = 1, which is indeed equal to the sum N=1 number.

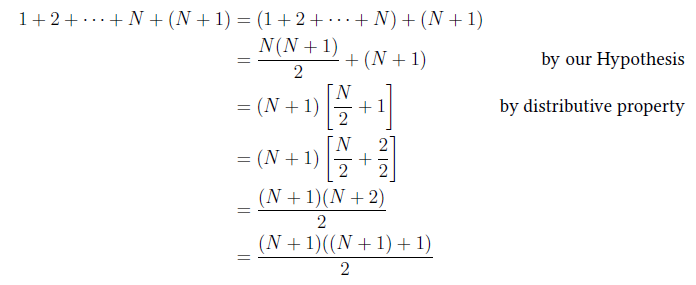

Our hypothesis: "Suppose that the sum of 1 + ... + N = N(N+1)/2 is true". Then, when we add N+1, we get the following:

And so, we showed that when we have k=N+1, we still have (N+1)((N+1)+1)/2 = k(k+1)/2.

Now this is really helpful! Instead of having to do N different additions, we just have to do 1 addition, 1 multiplication, and 1 division! That is way faster for humans and computers when N is really big! Cool!

Uploaded 2021 January 30. This is a part of a monthly project which you can read about here.

Special thanks to George Nasr (his ResearchGate) for helping proofread this, and bigger thanks to the non-math people I forced to read this to see if it was viable for a non-math audience.