For this month, I decided to solve two equations with one solution (the math version of two birds, one stone). This essay is my final paper for my Pedagogy class, where the prompt was "write a narrative about how your teaching philosophy has changed throughout the course of this semester". I thought it was fitting as an end of the year piece. It’s not necessarily “you’ll learn a new math thing today” like the other essays, but I think you’ll still take something away.

University of Minnesota’s Center for Educational Innovation defines teaching philosophy as a “self-reflective statement of your beliefs about teaching and learning” (“Writing Your Teaching Philosophy”, 2021). I am choosing to interpret this as “what are the important parts of what drives your teaching day-to-day?” With that, this is a narrative of how my teaching philosophy formed. I wanted to focus on this semester’s growth, but the build up to this semester adds both context and a couple hundred more words.

It is difficult to pinpoint when I transitioned from helping peers to becoming a “teacher”. I was a Peer-Learning Facilitator for AAP at UCLA, a title meant to emphasize that I am not a tutor nor a teacher. As such, I saw the task as more of a review session with students who wanted to strengthen their understanding of the material. I was not teaching, but the experience helped me see the different ways students learn.

It was only during this semester that I found the pedagogy terms that captured what I saw back then. The most prominent way students learned in my group aligned with how constructivism claims learning happens, where “people build mental models to make sense of their world” (Tsay & Hauk, 2013). It was an introductory physics course on mechanics. I often compiled physics problems to work on that had an approachable way of imagining it, allowing students to build actual mental images of the scenarios we were given. Thus, the fitting interpretation of the process fits in the constructivist view.

Last year, my duty was in recitations, a time to run through problems and discuss material students should have seen in the previous lecture. However, that did not stop me from teaching and neglecting the “recitation” aspect. I know I made that mistake when a student answered the end-of-semester survey saying “I have slacked off multiple times in actual lecture[s] because I feel that I can learn perfectly well by listening to Johan”.

In retrospect, I should have been spending more time facilitating group work. However, the choice I made was ultimately motivated by the virtual classroom we were in. I wanted to make the awkward 75 minutes we met over Zoom as valuable as possible. If group work could not prosper, I took on more of a teaching role. It did feel less genuine, I was just using time to sprint through material and rarely making room for absorption and synthesis. I say all this, to set the stage to say that my teaching philosophy before this semester was hierarchical. I gave information to students as a leader and students just did individual work.

A week before the semester started, I felt anxious about teaching. On one hand, I felt scared that I may not actually like teaching when I was given the reins to teach instead of assist. I discussed this anxiety in more detail in November - Unpack Teaching (Cristobal, 2021). While on the other hand, I felt scared that I would not be able to convince students to buy into my teaching.

On the second day (first official lecture as the first day was syllabus day), I opened with "my goal today is to convince you that coming to lecture is still worth your time," even if they can teach themselves with the online materials this class has. I believe you can view this declaration in two ways.

In one way, I was anxious about students liking me since it was my first time doing this officially. I wanted to show them that I am a serious individual, capable of standing on the stage, on the hierarchy, I thought I had.

The other, I was already fighting the old philosophy. I was not the all-knowing leader that gets to dictate what the students do with their time. Intermediate Algebra does its best to incentivize students to come to class, giving 20% of the grade to participation and exit tickets. However, even with that, that is still not enough. (I do not remember what made me realize this, perhaps my own experiences with skipping classes at UCLA.) College instructors have to market themselves to students. Unlike the K-12 system, college students are free to skip class (to their detriment), but missing class is usually never enough for a student to fail. Therefore, I unconsciously realized that I needed to step down from the high horse and confess to my students that I am a valuable asset, that my 50-minutes with them is valuable.

At the end of the class, I asked them if I had convinced them. They agreed and I said "see you next class." I did not have to be a stalwart person on the board commanding these students. I realized that they were already aware that I have the credentials to teach them. The mission was less about convincing students that they will learn something from me, but that their time and effort is valued in my classroom. My teaching philosophy was destroyed and reformed, this time with honesty and respect integral to the experience. It was just the second day of teaching.

A few weeks passed and at this point, my teaching philosophy could be summarized to “I have to be honest and sincere. Respect the time and effort students put in. Students need to walk out of every lecture feeling like those 50 minutes were worth getting up for.”

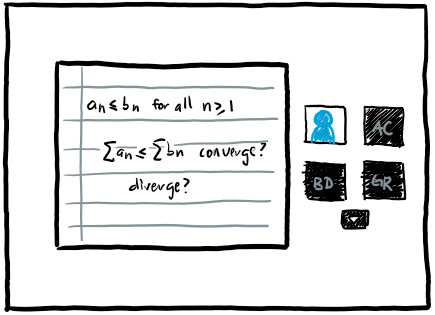

In the pedagogy course, we read about the four different levels in which classroom activities can run. The paper “Mathematics Graduate Teaching Assistants’ Question Strategies” talked about four levels in which mathematics instructors interact with questions within the classroom, both as the asker and and the asked (Roach, et. al., 2010). The lowest is Level 0, where the teacher is the only one asking questions which are mostly yes-or-no questions. While the highest is Level 3, where the teacher observes students, as the students learn from each other through sharing their thought processes. Level 3 is where "why?" becomes natural to ask.

I may have lost myself within the words: co-learner and co-teacher, because I made it a mission to create an environment of Level 3. I wanted to learn alongside students, since this was my first semester of teaching.

So, I took this idea of co-learning and ran with it (maybe past the conventional limit). I started to view each day of teaching as a way to learn how to teach that topic in tandem with my students learning said topic. For my teaching philosophy above, add "learn alongside students for the sake of organic flow". This worked well. My students rarely suspected that I was barely preparing anything for class. I based the day’s goals based on issues and questions brought up the day before, never doing the problems ahead of time.

Enter the Applications of Linear Equations section. There were a lot of word problems and as with tradition, these got tricky. I had not prepared ahead of time besides knowing that this section would be difficult for students. I just did not think it would be difficult for me as well. The first problem stumped me with the wording. I spent way more time trying to crawl my way out rather than moving on.

This mishap went against my teaching philosophy. For the first time in the semester, I felt like I wasted students' time. I drew back. I confessed to the students that I have not been preparing for lectures for the past few sections. I told them that it felt more organic to learn alongside them rather than already knowing the answers. We resorted to working on homework problems after that, with the promise that I would come back more prepared.

I still enjoyed the idea that I am supposed to grow alongside students, but I understood that I cannot go blindly. I reeled in my lofty philosophy, instead adding “Find balance between preparing material and organically doing problems along with students, being mindful of the bumps and errors that could arise ahead of time”.

As it stood, my teaching philosophy centered around the student experience. The being known as Johan was not accounted for in this new Johan Teaching Philosophy, at least not yet. I did not think I had to be included in how I viewed my teaching philosophy, since it should be about the students, their learning and experience.

However, my personal experience and relationship with teaching played an unnoticed role in how I interacted with students. Years after years of convincing myself that failure is a bigger learning moment than success itself, I am still scared of it. I started carrying this anxiety that my students are going to fail, after something small like missing one assessment (even when they can retake it the next week). This has its own ten-page paper story that is waiting to be written, but for now we will glide past it.

This fear came to a climax when I realized that I was more worried about their grades than how I was doing in my own courses. The ugly truth is that not everyone will pass a (math) class. There are countless factors that could sidetrack students that are out of their control, especially given these pandemic times. I had to learn that I can only stretch myself so thin for my students to be successful. It hurt to accept, it felt like I was killing the students’ potential to pass when I stopped constantly emailing them and begging them to do their work.

There are two things that pushed me to make this decision. After discussions with other instructors, it became apparent that I was stretching myself thin. My attention drifted from the students who are still trying, and I started to dread the experience of teaching. The quality of my lecture lessened. I was more worried about student grades than student learning. It started to sour the entire group.

The second is that students’ autonomy became compromised. During a discussion in pedagogy, I realized I may have been preventing students from learning to be independent, to be more in charge of their learning. In a way, Intermediate Algebra is the best time for students to develop their system of balance between school, work, and personal life. It moves at a kind pace, the Canvas page is organized with a weekly calendar on the homepage, and the pattern of assignments allows students to get a rhythm. By “coddling” students, I hindered their process of learning how to remember, manage, and prioritize their responsibilities.

I do not mean to imply that I should stop any effort to remind students, but it should be balanced. I believe writing reminders on the board for things that need to be done before we meet again should be the extent of my reminders. I reached this point where balance is a keyword that I keep coming back to. Therefore, I add to my teaching philosophy, to highlight myself and how I stand as a player in this game, “Be mindful of your health, a tired teacher is not a good teacher. Find balance between giving students the chance to grow freely and guiding them to a good path.”

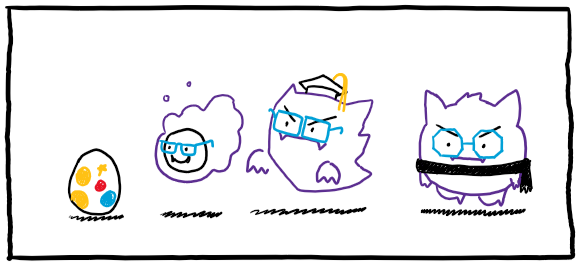

I have never taught before becoming a Facilitator, that much is true. However, to say that I had no teaching experience or teaching philosophy would be untruthful. I would not be in grad school if I did not have any philosophy driving me through the application, the pandemic, and all chaos these past two years have been.

I am an observer and I internalize behavior and knowledge. Dr. Rolando De Santiago did far too much for my development philosophy. He was the first math professor I had that was aware of the often-unsaid influence of identity in being a student in math. I was in awe. Up until that moment, I expected my mathematics courses to run the same dryness it had been for years. I sat in one of his classes since I had class right after. I was curious about what made his lectures easier to follow, what was his teaching style, how were his exams written, and all other questions. So, I observed. The mannerisms, the way his personality comes and goes within lecture, and how he always ends the quarter sharing his story.

I internalized it, while adding some Johan, Generation Z-lennial twist to it. Then, I was given the chance to be a Facilitator for AAP at UCLA. In short, AAP is UCLA’s campus organization for underrepresented students, often first generation or low-income, where they can seek mentorship and opportunities designed for them. They emphasized the importance of identity and one’s personal histories as they play an integral role in their education and success during and after college. I add to my philosophy: “Create an environment where you would want to learn and to be seen as a scholar, and not just a statistic.

Related to the topic of failure is the topic of difficulty. I struggled in Physics which made me a better Facilitator, since I genuinely knew how to struggle within that world. On the other hand, math has more-or-less been kind to me. So when I say, “this is hard, so it’s okay to get tripped up,” it does not feel genuine. After some self-organizing and writing my thoughts for August - Re: Math is Hard, I landed on a nice mantra that “math is hard, but not forever” (Cristobal, 2021). It is a statement I can genuinely convey; admitting that it is difficult, but accepting that it is not the final state. My sister put it nicely that “nothing worthwhile has ever come easy.” So, I add to my philosophy: “Learning can be difficult, but you cannot separate difficulty from learning.”

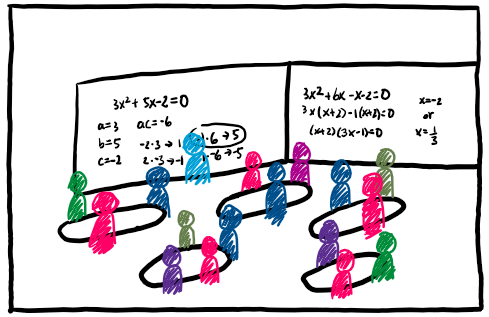

My pedagogy professor referred me to the term “social constructivism”. In a poetic sense, it is like constructivism (knowledge is built internally as students create their own systems of relationships) but with heart (conscious awareness that learning happens in a community.) Using Berkeley Graduate Division’s summary of Lev Vygotsky’s work, we see the heavy emphasis placed on collaborative work. This is easier said than done, since it is still difficult to have students buy-in to the idea that their group struggle and work is as fruitful as my lectures. That brings me to another addition to my philosophy, “My teaching is always in motion. Just because I do not know how to do something now, it doesn’t mean I can’t do it later.”

Lastly, my favorite book through the pandemic, “Mathematics for Human Flourishing” by Dr. Francis Su. To those that know me, this is not a surprise. I talk about this book so much. In short, this book realigned what it meant for me to enjoy math. So, I add one last important thing to my teaching philosophy: “Growth is inevitable, just as much as failure is. Enjoy this process. Play, love, and flourish in the math explorer’s world.”

In a way, my teaching philosophy circled back to the same observed and internalized form, but not quite in the same way as in my Facilitator days. For one, I am actually teaching instead of reviewing. In another way, it has become more sophisticated. Having a teaching philosophy be destroyed within the first week was necessary. It allowed for a new philosophy to be created from the ground up, rather than bestowed upon by circumstances. The beauty being that there will always be room to grow, learn, and improve.

To save you the scrolling and scavenger hunt, my teaching philosophy in one place:

“I have to be honest and sincere. Respect the time and effort students put in. Students need to walk out of every lecture feeling like those 50 minutes were worth getting up for. Find balance between preparing material and organically doing problems along with students, being mindful of the bumps and errors that could arise ahead of time. Be mindful of your health, a tired teacher is not a good teacher. Find balance between giving students the chance to grow freely and guiding them to a good path. Create an environment where you would want to learn and to be seen as a scholar, and not just a statistic. Learning can be difficult, but you cannot separate difficulty from learning. The most difficult things in life tend to be the most cherished. My teaching is always in motion. Just because I do not know how to do something now, it doesn’t mean I can’t do it later. Growth is inevitable, just as much as failure is. Enjoy this process. Play, love, and flourish in the math explorer’s world.”

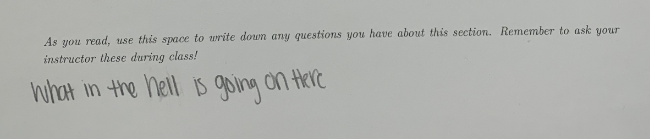

Here's my favorite quote from a student's work.

[1] Berkeley Graduate Division. (n.d.). Social Constructivism. Graduate Student Instructor Teaching & Resource Center. Retrieved December 6, 20201, from LINK

[2] Cristobal, J. (2021). November - Unpack Teaching. LINK

[3] Cristobal, J. (2021). August - Re: Math is Hard. LINK

[4] Roach, K., Roberson, L., Tsay, J., & Hauk, S. (2010). Mathematics Graduate Teaching Assistants’ Question Strategies. Proceedings of the 13th Annual Conference on Research in Undergraduate Mathematics Education. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from LINK

[5] Su, F. (2020). Mathematics for Human Flourishing. Yale University Press.

[6] Tsay, J., & Hauk, S. (2013). Constructivism. Video cases for college mathematics instructor professional development. Retrieved December 6, 2021, from LINK

[7] Center for Educational Innovation. (2021). Writing Your Teaching Philosophy. University of Minnesota. Retrieved December 6, 20201, from LINK

Uploaded 2021 December 17. This is a part of a monthly project which you can read about here.

Special thanks to my pedagogy professor Dr. Joshua Brummer (his website), and bigger thanks to my Intermediate Algebra students who let me learn alongside them.